2016 Motivating Values and Constancy of High-Intensity Female Supporters of Donald Trump

Anne Segal and Jack Sorock

January 25, 2017

Anne Segal and Jack Sorock are researchers with The Frontier Center

A R T I C L E I N F O

Research history:

Qualitative research conducted July 2016 though December 2017.

Survey conducted between 5 December 2016 and 2 January 2017

Keywords:

Brand equity, Politics, Research

A B S T R A C T

For this study, female supporters of Donald Trump as a candidate for U.S. President shared their views on what drives their connection to him. This information was used to produce a comprehensive summary of the patterns that explain why this panel of women support Donald Trump, identifying the values “Community,” “Relatable/Anti-Elitism,” “Coarseness/Strength,” “Active Optimism,” and “Empowerment (Exuberance of Freedom),” as well as the underlying observations about Donald Trump that provide the foundation for these deeply felt connections. A survey was also conducted using a panel of 315 women who self-reported their intensity of support for Donald Trump as a “7” on a scale from 1 -7 in order to answer the following questions: when did they begin to support Donald Trump, did their support ever waver, and what other demographic insights can we learn about this panel of women.

1. EXPLANATIONS FOR FEMALE TRUMP SUPPORT

Support among women for the candidacy of Donald Trump for president in 2016 has been attributed to sexism, personal fears about the economy, xenophobia, and racism, including “fears about their husbands’ jobs” (Roberts and Ely, 2016), among other hypotheses – extrapolated from exit-polling data taken on the day of the U.S. presidential election, November 7, 2016. An analysis of 315 panel survey responses and 20 laddering interviews taken over 120 hours with high-intensity female supporters of Donald Trump indicates that five underlying values drive connection to the candidacy and brand of Donald Trump among this panel of women. A description of the patterns that emerged as well as implications for how these insights can complement understanding of Donald Trump’s brand equity are also provided.

1.1 Available Analysis Based on Limited, Flawed Data

Explaining female support for Donald Trump in the context of his candidacy for U.S. president has proved challenging for analysts, pundits, and thought leaders. Data underscoring this understanding has been limited to exit-polling conducted by Edison Research on behalf of the National Election Pool (NEP), which represents the six major news networks in the United States, and indicates that women supported Clinton over Trump 52% to 42% (contrast this to the exit poll data on 2012, when 55% of women supported Obama and 44 Romney; and 2008, when 56% of women supported Obama and 43% of women supported McCain). A handful of surveys conducted over the course of the 2016 election campaign, including a YouGov survey examining theories about the role of sexism in shaping the white vote, failed to provide insight into how women voted (Schaffner, MacWilliams, and Nteta, 2017).

Moreover, there is at least the plausibility of concern not only about the accuracy of exit polling in the 2016 election due to the “silent,” “hidden,” or “shy” voter theory, which posits that Trump voters may not have accurately represented themselves to exit pollsters (Claassen and Ryan, 2016). Concerns about the accuracy of polling methodologies, evidenced by inaccurate forecasting over the past several election cycles and perhaps most strikingly captured by statistician Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight.com giving Hillary Clinton a “99% chance of winning,” cast serious doubt on the quality of insight into the motivating drivers behind women support for Donald Trump.

In summary:

Explanations offered for Trump’s female support are based on exit polling data and election surveys.

Conclusions jump from demographic data and limited surface-level questions to broad generalizations about the mindset of female Trump supporters.

This is the first study undertaken to seek the in-depth patterns of behavior and attitude among high-intensity female Trump supporters.

It is for this reason that The Frontier Center conducted a comprehensive study with a panel of high-intensity female Trump supporters, including in-depth qualitative interviews and a survey instrument.

1.2 Methodology for this Study

We first conducted hour-long, in-depth “Laddering” interviews based on the Means-End Theory (Gutman, 1982), with 16 female supporters of Donald Trump. The interviewees were recruited from a discrete pool of self-identified women supporters of Trump (47,081) who were “followers” of the “Women for Donald Trump” Facebook page, of whom we spoke with those meeting the following criteria: voted for Trump in the primary (if a primary was in fact held), voted for Trump in the general, and rated their support for him as a "7."

We then conducted a panel survey, drawn from the same audience of 47,081 females, of 315 self-identified, female, high-intensity supporters of Donald Trump. Our data set was 82.2% Caucasian and 43.8% college-educated. It is important to note that the Laddering methodology and panel survey data are not sampling-based methodologies but rather techniques to develop insights about a discrete pool of individuals with shared characteristics (female, high-intensity support for Donald Trump, and fans of his on social media). More information about Laddering and Panel Data can be found in the sources cited.

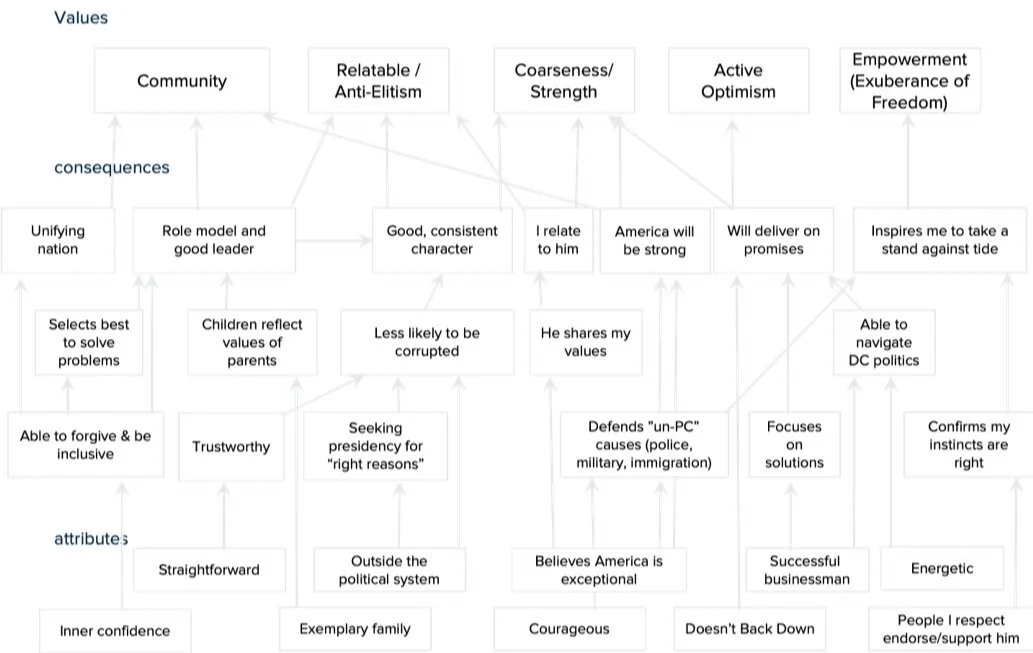

Figure 1 Hierarchical Value Map of Female Trump Supporters

2. VALUES THAT EXPLAIN FEMALE CONNECTION TO TRUMP

Five distinct values, or underlying emotional planes, explain high-intensity support for Donald Trump among the females we interviewed: “Community,” “Relatable/Anti-Elitism,” “Coarseness/Strength,” Active Optimism,” and “Empowerment (Exuberance of Freedom).” (Fig. 1)

2.1 Community

Donald Trump provided women with a sense of pride in their country, a value that flowed in part from their understanding that because he has the confidence to surround himself with diversity of thought – choosing those who are best at solving problems, not simply those who are loyal. This ability to forgive those who may not have been supportive in the past (for example, including Reince Priebus in his cabinet), signalled to them that he would be a good leader – the consequence of which is increased standing of our nation.

At the same time, they viewed his “exemplary family” as an indication that he had been a good parent, leading them to see him as both a good role model for themselves personally, and a good leader for the country.

Finally, women’s sense of pride in country stemmed from Trump’s articulation of his firm belief that “America is good,” alongside his willingness (bolstered by his courageous, straightforward nature) to defend those institutions that will make America strong: primarily the military, police, and our borders.

2.2 Relatable/Anti-Elitism

While the prevailing narrative in our media is that Trump is perceived as having been born with a “silver spoon in his mouth,” to the contrary, high-intensity female supporters women found Trump’s relatability to be one of his most compelling dimensions. From his role as a father who raised exemplary children to the unapologetic reflection of shared values with these women, it was the perception of relatability that drove his appeal.

How would the family of a billionaire lead someone to the conclusion that the billionaire was relatable? In this case, Trump’s family members acted as poster-children for the values and traits these women valued and sought after in their own families. As a unit, women recounted to us that Trump’s family projected an air of solidarity throughout the various struggles that plagued Trump’s campaign. They were supportive of Trump and his agenda, despite likely differences of political opinion amongst them.

As individuals, women found that each of Trump’s children displayed the fruits of hard work, dedication, humility and eloquence—both in their private lives and as advocates for Trump on the campaign trail. Because women reasoned that these characteristics in Trump’s children must have been instilled in them at least partially by Trump himself, women related to his dedication to family on a deep, visceral level. It was not only a supportive and exemplary family that mirrored their understanding of what a good family should look like, but it also more poignantly represented to them in their desire to instill in the next generation the values they had learned to live by and cherish.

In addition, women indicated that because Trump was from outside the political system, and therefore seeking the presidency for the “right reasons,” they trusted his character – and felt they could relate to him. A life outside the beltway is more akin to that of the everyday American, rather than inside. Women said that “inside-the-beltway” politicians felt less dependable, whom they had seen shuffle their priorities from those promised to their constituents to those of lobbyists, and whose values were malleable enough to bend in pursuit of political power. Such a politician, according to these women, could not be a man of the people.

On the other hand, it was Trump’s real-world experience and family that gave women confidence that Trump would be able to enter the political realm and, at the outset, prioritize their (i.e. his) concerns. Women saw his straightforward, matter-of-fact temperament, his ability not to cower to anyone, and having owed no favors to anyone in Washington, as indications that his priorities could remain as he initially promised.

Together, these attributes of Trump’s relatability indicate that, when it comes to his high-intensity female supporters, there is more connection to be found in shared values and the likelihood of constancy than in comparing the size of bank accounts.

2.3 Coarseness/Strength

Coarseness/Strength was a driving motivator in connecting women to Trump, both in terms of their personal safety as well as the security of the nation. With regards to strength, women appreciated Trump’s willingness to defend causes that, while controversial to some, would have tangible and proximate effects on the local, personal level: defending the police, defending the military, and defending the border. Each time Trump positively communicated his support and appreciate for these institutions, women manifested a desire for strength and the coarseness in directly saying he would provide this. Similarly, Trump’s insistence that America is not only worth preserving, but also good, reinforced their belief that Trump would fight for our nation’s security.

Women’s perception that Trump would deliver on his promises by effectively navigating D.C. politics provided additional confidence that Trump both sought a strong America again and had the wherewithal to accomplish that goal. That women saw Trump as possessing the requisite traits as a man of character, a role model in the family, and an inclusive delegator, strengthened their confidence that he could execute his vision throughout the federal government and thus maintain people’s trust.

Despite concerns voiced from opponents about Trump imperiling the nation through his “access to the nuclear launch codes,” the women in this study felt the converse: that it was precisely because of Trump’s character that they both trusted him and expressly desired that it was he who would be given that responsibility.

2.4 Active Optimism

Women felt a sense of Active Optimism resulting from their estimation that Trump would be able to fulfill campaign promises. To them, the ability to deliver on his promises stemmed not only from his strength and resolve in not backing down, but also from his skill at navigating the D.C. political environment. That skill was evidenced to women in two ways: first, through Trump’s energy and vigor on the campaign trail, and second, through his track record of success as a businessman. Trump’s business experience also flowed into a feeling of Active Optimism as, according to women, it made Trump more focused on solutions as opposed to simply saying the right thing.

2.5 Empowerment (Exuberance of Freedom)

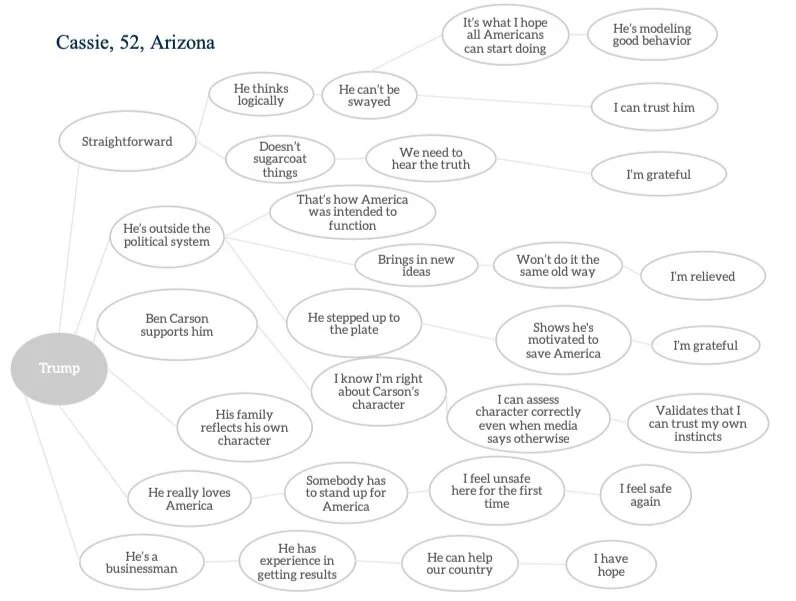

The final value identified as driving support for Trump among high-intensity females was that of “empowerment.” Women related that, while in the past they may have held certain opinions, there was now a far more acute desire to take a stand in defense of those opinions. The role of endorsements was central to the confirmation of their opinions; when prominent politicians or other individuals the women respected endorsed Trump, it had the effect of confirming to them that their own instincts were right. For example, one woman recounted that when Ben Carson endorsed Trump, she thought, “Well, I know I’m right about Ben Carson’s character – so when he endorsed Trump I realized that I had been judging everything right after all – despite the media making me think I had it all wrong!” This realization led to her being validating in trusting her own instincts – and rejecting those of the prevailing culture who thought otherwise of Trump. For this reason, there is ample evidence to conclude that the role of endorsements in the 2016 election may have had an even stronger effect than in the past, given the unique positioning Trump held in stark opposition to the media’s narrative.

3. PANEL DATA INSIGHTS

For the panel study, 315 high-intensity female supporters of Donald Trump completed a nationwide online survey. We recruited participants for the survey from the “Women for Donald Trump” Facebook page, and asked them to share a link to the survey with their friends. The survey assessed current level of support for Trump, when that support developed, if that support ever waned, party affiliation currently and prior to the election, overarching reasons for their support, as well as gathered media consumption habits and demographic insights.

“High-intensity” was measured with the questions, “Who did you vote for in the 2016 presidential election?” and “On a scale of 1-7, how would you describe your current level of support for Donald Trump as president? (1 – very against, 4 – neither against nor supportive, 7 – very supportive)” Participants who identified as female, indicated that they had voted for Trump in the general election and were a “7” in terms of intensity of support, were considered to be “high-intensity.”

73% of our panel had voted for Donald Trump in the primary in addition to voting for him in the general. An additional 11% did not vote in the primary at all, 5% voted for Ted Cruz and 4% voted for Ben Carson. Four women had voted in the primaries for Bernie Sanders, and one had voted for Hillary Clinton.

Figure 2 Sample Laddering Interview Flowchart

3.1 Changes in Party Affiliation

Reviewing the movement between party labels among our panel of women reveals that while the those who affiliated as Republicans increased overall, there was more shuffling beneath the surface than this figure may indicate. Overall, 63% of our panel considered themselves “Republican” prior to the election, which increased to 65% at the time of our survey (conducted in late December 2016).

First, the Democrats: 6% of our panel had considered themselves Democrats prior to the election, and of those, 65% switched to affiliate as Republican and 25% switched to affiliate as Independent.

Those affiliating as Independent slightly decreased from 26% prior to the election to 23% at the time of our survey. Of those who had considered themselves Independent, 35% switched their affiliation to Republican.

And of those who had affiliated as Republican prior to the election, 13% left the party and either now refer to themselves as Independents (8%) or ceased using the label Republican (6%) for various reasons. Thus, while many high-intensity female supporters of Trump on our panel joined the Republican label post-election, a portion of those who ha been Republicans before changed affiliation as well.

3.2 Timing and Origins of Support

While a majority of women in our panel (65%) had made up their mind to support Trump from the very beginning, the next most popular time to have made up their minds was when their preferred candidate dropped out (12%). An additional 10% made up their minds after the first debate.

Our panel indicated that it was more important to them that the candidate they supported shared their opinions (65%), not the one with whom they agreed and felt would be able to “win” (26%). (This is helpful in evaluating messaging by opponents of Trump that he “couldn’t win,” which may have not been an impactful way to try to dissuade high-intensity female supporters from their support.)

3.3 Constancy of Support

The women of our panel were extremely loyal to Donald Trump: 95% reported that they never considered withdrawing their support for him throughout the entire election season.

94% of the Independent subset never considered withdrawing their support for him, and 88% of that same subset did not think any of Trump’s shortcomings strongly affected, or affected at all, their support for him.

3.4 Media Habits

We asked our panel where they watched the results come in Election Night: 65% watched Fox News, followed by 7% who watched Fox Business. 7% said they skipped between channels constantly or didn’t watch at all.

4. RESEARCH IMPLICATIONS

The data gathered through the Laddering methodology for in-depth interviews and accompanying panel survey insights from 315 high-intensity Trump supporters cast doubt on analysts’ and pundits’ conclusion that female support for Trump is drawn by racism, sexism, and “fears about their husbands’ jobs.” In order to adequately begin to uncover how the Trump political brand functioned in the past, this examination of high-intensity supporters provides an initial grounding in connections based on affiliation with character traits, connection on a personal level, Active Optimism, and as a source of self-affirmation despite the prevailing mainstream narrative that he was none of these things to women.

The larger implication is that the analysts continue to “get it wrong” when it comes to choosing the best methodologies for uncovering actionable and accurate insights about the hearts and minds of the American electorate. And, for those seeking to weaken the support of Trump, the empowerment of “Trump women” through his successes will only grow—and further distances these women from the idea that they belong to or identify with another candidate or political brand.

REFERENCES

Roberts, L. and Ely, R. (2016), “What’s Behind the Unexpected Trump Support from Women”, Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.

Schaffner, B., MacWilliams, M., & Nteta, T. (2017), “Explaining White Polarization in the 2016 Vote for President: The Sobering Role of Racism and Sexism”, Conference on The U.S. Election of 2016: Domestic and International Aspects, IDC Herzliya Campus.

Claassen, R. and Ryan, J. (2016), “Social Desirability, Hidden Biases, and Support for Hillary Clinton”, PS: Political Science & Politics.

Gutman, J. (1982), “A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization process”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 42, pp 60-72.